- Serena Krombach

- Jan 18, 2024

- 2 min read

Updated: Jan 19, 2024

Children are often so excited to tell adults their accomplishments: "I cut my bagel all by myself!" "Look how high I am!" "Let me tell you all the volcanoes I went to when I went to Iceland!" We will, of course, have them tell us more about what they did and how they did it, and listen patiently to what they know—congratulating them and reinforcing the pride they should feel in themselves. In Sideways School, though, we direct the child to turn to their friends instead, and something different happens:

M.: "I cut my bagel all by myself!"

L.: "Well yesterday I cut all the strawberries all by myself!"

They get to know themselves not only as the superstars we see them as, but as part of a cohort, all learning and achieving and discovering new abilities.

C.: "Look how high I am!"

R.: "Great job!"

Children learn and can use the language of praise, if we let them! And how much more validating might it be for a child to hear this from a peer than from a grownup?

Q.: "Let me tell you the all the volcanoes I went to when I went to Iceland."

K.: "No thanks." [Walks away.]

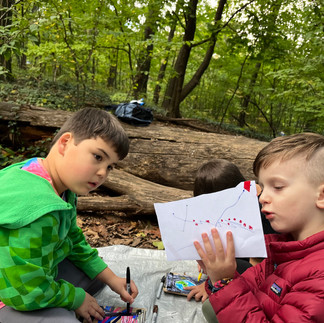

K. has a totally age-appropriate response, and we'll deal with that later. But now Q. has no one with whom to share his knowledge, and hurt feelings. This is a great moment for grownup to take off their invisibility cloak and step in with a suggestion—one that the child might take to heart for the next time: "What about drawing the volcanoes?" Q. gets to express what he knows in a different way—and it turns out that showing rather than telling achieves real interest from a peer, and an even more satisfying reaction. And because the children have time to play, the volcano map gets woven into game: the explorers find themselves on an underwater volcano and need a map to navigate a path to safety before it blows!

When children share their exciting news and knowledge with each other, they get so much more than they might from grownups. They get meaningful interaction that, in turn, can lead to deep learning about themselves, as well as deeper connections with the peers who are learning, living, and growing alongside them.